Abstraction - Classes

Term object means (in object-oriented programming) loosely collection of data with a set of methods for accessing and manipulating them.

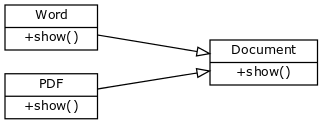

Polymorphism

Sometimes an object comes in many types or forms. If we have a button, there are many different draw outputs (round button, check button, square button, button with image) but they do share the same logic: onClick(). We access them using the same method . This idea is called Polymorphism.

Polymorphism is based on the greek words Poly (many) and morphism (forms).

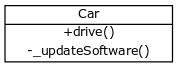

Encapsulation

Encapsulation is the principle of hiding unnecessary details from the rest of the world.

In an object oriented python program, you can restrict access to methods and variables. This can prevent the data from being modified by accident and is known as encapsulation.

#!/usr/bin/env python

class Car:

def __init__(self):

self.__updateSoftware()

def drive(self):

print('driving')

def __updateSoftware(self):

print('updating software')

redcar = Car()

redcar.drive()

#redcar.__updateSoftware() not accesible from object.We create a class Car which has two methods: drive() and updateSoftware(). When a car object is created, it will call the private methods __updateSoftware().

This function cannot be called on the object directly, only from within the class.

Inheritance

Classes can inherit functionality of other classes. If an object is created using a class that inherits from a superclass, the object will contain the methods of both the class and the superclass. The same holds true for variables of both the superclass and the class that inherits from the super class.

Python supports inheritance from multiple classes, unlike other popular programming languages.

class User:

name = ""

def __init__(self, name):

self.name = name

def printName(self):

print("Name = " + self.name)

class Programmer(User):

def __init__(self, name):

self.name = name

def doPython(self):

print("Programming Python")

brian = User("brian")

brian.printName()

diana = Programmer("Diana")

diana.printName()

diana.doPython()Output:

Name = brian

Name = Diana

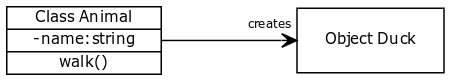

Programming PythonClasses

All objects belong to a class and are said to be instances of that class.

class Animal:

def __init__(self,name):

self.name = name

def walk(self):

print(self.name + ' walks.')

duck = Animal('Duck')

duck.walk()Another example:

class Person:

def set_name(self, name):

self.name = name

def get_name(self):

return self.name

def greet(self):

print("Hello, world! I'm {}.".format(self.name))>>> foo = Person()

>>> bar = Person()

>>> foo.set_name('Luke Skywalker')

>>> bar.set_name('Anakin Skywalker')

>>> foo.greet()

Hello, world! I'm Luke Skywalker.

>>> bar.greet()

Hello, world! I'm Anakin Skywalker.The attributes are also accessible from the outside.

>>> foo.name

'Luke Skywalker'

>>> bar.name = 'Yoda'

>>> bar.greet()

Hello, world! I'm Yoda.Attributes, functions and methods

The self parameter is, in fact, what distinguishes methods from functions. Methods have their first parameter bound to the instance they belong to, so you don’t have to supply it. While you can certainly bind an attribute to a plain function, it won’t have that special self parameter.

Privacy

By default, you can access the attributes of an object from the “outside.” But it breaks principle of encapsulation.

To make a method or attribute private (inaccessible from the outside), simply start its name with two underscores.

class Secretive:

def __inaccessible(self):

print("Bet you can't see me ...")

def accessible(self):

print("The secret message is:")

self.__inaccessible()Now inaccessible is inaccessible to the outside world, while it can still be used inside the class (for example, from accessible).

>>> s = Secretive()

>>> s.__inaccessible()

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module>

AttributeError: Secretive instance has no attribute '__inaccessible'

>>> s.accessible()

The secret message is:

Bet you can't see me ...In fact, there is a way to access "hidden" methods:

>>> s._Secretive__inaccessible()

Bet you can't see me ...But you really shouldn't do it!

Class namespace

class MemberCounter:

members = 0

def init(self):

MemberCounter.members += 1

>>> m1 = MemberCounter()

>>> m1.init()

>>> MemberCounter.members

1

>>> m2 = MemberCounter()

>>> m2.init()

>>> MemberCounter.members

2In the preceding code, a variable is defined in the class scope, which can be accessed by all the members (instances), in this case to count the number of class members.

This class scope variable is accessible from every instance as well, just as methods are.

>>> m1.members

2

>>> m2.members

2What happens when you rebind the members attribute in an instance?

Superclass

Subclasses expand on the definitions in their superclasses. You indicate the superclass in a class statement by writing it in parentheses after the class name.

class Filter:

def init(self):

self.blocked = []

def filter(self, sequence):

return [x for x in sequence if x not in self.blocked]

class SPAMFilter(Filter): # SPAMFilter is a subclass of Filter

def init(self): # Overrides init method from Filter superclass

self.blocked = ['SPAM']Filter is a general class for filtering sequences. Actually it doesn’t filter out anything.

>>> f = Filter()

>>> f.init()

>>> f.filter([1, 2, 3])

[1, 2, 3]SPAMFilter will filter 'SPAM' sequence:

>>> s = SPAMFilter()

>>> s.init()

>>> s.filter(['SPAM', 'SPAM', 'SPAM', 'SPAM', 'eggs', 'bacon', 'SPAM'])

['eggs', 'bacon']Inheritance

If you want to find out whether a class is a subclass of another, you can use the built-in method issubclass.

>>> issubclass(SPAMFilter, Filter)

True

>>> issubclass(Filter, SPAMFilter)

FalseIf you have a class and want to know its base classes, you can access its special attribute bases.

>>> SPAMFilter.__bases__

(<class __main__.Filter at 0x171e40>,)

>>> Filter.__bases__

(<class 'object'>,)You can check whether an object is an instance of a class by using isinstance.

>>> s = SPAMFilter()

>>> isinstance(s, SPAMFilter)

True

>>> isinstance(s, Filter)

True

>>> isinstance(s, str)

FalseUsing isinstance is usually not good practice. Relying on polymorphism is almost always better.

If you just want to find out which class an object belongs to, you can use the class attribute.

>>> s.__class__

<class __main__.SPAMFilter at 0x1707c0>Multiple superclasses

class Calculator:

def calculate(self, expression):

self.value = eval(expression)

class Talker:

def talk(self):

print('Hi, my value is', self.value)

class TalkingCalculator(Calculator, Talker):

passThe subclass (TalkingCalculator) does nothing by itself; it inherits all its behavior from its superclasses. The point is that it inherits both calculate from Calculator and talk from Talker, making it a talking calculator.

>>> tc = TalkingCalculator()

>>> tc.calculate('1 + 2 * 3')

>>> tc.talk()

Hi, my value is 7You must be careful about the order of these superclasses (in the class statement). The methods in the earlier classes override the methods in the later ones. So if the Calculator class in the preceding example had a method called talk, it would override (and make inaccessible) the talk method of the Talker.

This wouldn't work:

class TalkingCalculator(Talker, Calculator): pass